Ancient Macedonian language

- For the unrelated modern Slavic language, see Macedonian language.

Ancient Macedonian was the language of the ancient Macedonians. It was spoken in the kingdom of Macedon during the 1st millennium BC and it belongs to the Indo-European group of languages. It gradually fell out of use during the 4th century BC, marginalized by Koine Greek, the lingua franca of the Hellenistic period.[1]

Classification of the language is difficult, as it it is known from only a few fragmentary surviving attestations, mainly in glosses and proper names.[2]

A body of words has been assembled from ancient sources, mainly from inscriptions, and from the 5th century lexicon of Hesychius of Alexandria, amounting to about 150 words and 200 proper names. The volume of the surviving public and private inscriptions indicate that there was no written language in ancient Macedonia but Greek.[3]

Contents |

Classification

Macedonian is part of the Paleo-Balkans group within Indo-European. The phylogenetic relation of these languages in general is unclear, and the closeness of Macedonian to Greek in particular is subject to debate, a discussion closely related to the reconstruction of the Proto-Greek language. Due to the fragmentary attestation various interpretations are possible.[4] Suggested phylogenetic classifications of Macedonian include:[5]

- An Indo-European language which is a close cousin to Greek and also related to Thracian and Phrygian languages, suggested by A. Meillet (1913) and I. I. Russu (1938),[6] or part of a Sprachbund encompassing Thracian, Illyrian and Greek (Kretschmer 1896, E. Schwyzer 1959).

- An "Illyrian" dialect mixed with Greek, suggested by K. O. Müller (1825) and by G. Bonfante (1987).

- Various explicitly "Greek" scenarios:

- A Greek dialect, part of the North-Western (Locrian, Aetolian, Phocidian, Epirote) variants of Doric Greek, suggested by N.G.L. Hammond (1989) and O. Masson (1996).[7][8]

- A northern Greek dialect, related to Aeolic Greek and Thessalian, suggested among others by A.Fick (1874) and O.Hoffmann (1906).[7][9]

- A Greek dialect with a non-Indo-European substratal influence, suggested by M. Sakellariou (1983).

- A sibling language of Greek within Indo-European, Macedonian and Greek forming two subbranches of a Greco-Macedonian subgroup within Indo-European (sometimes called "Hellenic"),[4] suggested by Joseph (2001) and others.[10]

Properties

From the few words that survive, only a little can be said about the language. A notable sound-law is that the Proto-Indo-European voiced aspirates (/bʰ, dʰ, gʰ/) appear as voiced stops /b, d, g/, (written β, δ, γ), in contrast to all known Greek dialects, which have unvoiced them to /pʰ, tʰ, kʰ/ (φ, θ, χ) with few exceptions.[11]

- Macedonian δάνος dánοs ('death', from PIE *dhenh2- 'to leave'), compare Attic θάνος thános

- Macedonian ἀβροῦτες abroûtes or ἀβροῦϜες abroûwes as opposed to Attic ὀφρῦς ophrûs for 'eyebrows'

- Macedonian Βερενίκη Bereníkē versus Attic Φερενίκη Phereníkē, 'bearing victory'

- Macedonian ἄδραια adraia ('bright weather'), compare Attic αἰθρία aithría, from PIE *h2aidh-

- Macedonian βάσκιοι báskioi ('fasces'), Attic φάσκωλος pháskōlos 'leather sack' , from PIE *bhasko

- According to Herodotus 7.73 (ca. 440 BC), the Macedonians claimed that the Phryges were called Brygoi before they migrated from Thrace to Anatolia (around 8th–7th century BC).

- According to Plutarch, Moralia[12] Macedonians use 'b' instead of 'ph', while Delphians use 'b' in the place of 'p'.

- Macedonian μάγειρος mágeiros ('butcher') was a loan from Doric into Attic. Vittore Pisani has suggested an ultimately Macedonian origin for the word, which could then be cognate to μάχαιρα mákhaira ('knife', <PIE *magh-, 'to fight')

If γοτάν gotán ('pig') is related to *gwou ('cattle'), this would indicate that the labiovelars were either intact, or merged with the velars, unlike the usual Greek treatment (Attic βοῦς boûs). Such deviations, however, are not unknown in Greek dialects; compare Doric (Spartan) γλεπ- glep- for common Greek βλεπ- blep-, as well as Doric γλάχων gláchōn and Ionic γλήχων glēchōn for common Greek βλήχων blēchōn.[13]

A number of examples suggest that voiced velar stops were devoiced, especially word-initially: κάναδοι kánadoi, 'jaws' (<PIE *genu-); κόμβους kómbous, 'molars' (<PIE *gombh-); within words: ἀρκόν arkón (Attic ἀργός argós); the Macedonian toponym Akesamenai, from the Pierian name Akesamenos (if Akesa- is cognate to Greek agassomai, agamai, "to astonish"; cf. the Thracian name Agassamenos).

In Aristophanes' The Birds, the form κεβλήπυρις keblēpyris ('red-cap bird') is found, showing a Macedonian-style voiced stop in place of a standard Greek unvoiced aspirate: κεβ(α)λή keb(a)lē versus κεφαλή kephalē ('head').

A number of the Macedonian words, particularly in Hesychius' lexicon, are disputed (i.e., some do not consider them actual Macedonian words) and some may have been corrupted in the transmission. Thus abroutes, may be read as abrouwes (αβρουϝες), with tau (Τ) replacing a digamma.[14] If so, this word would perhaps be encompassable within a Greek dialect; however, others (e.g. A. Meillet) see the dental as authentic and think that this specific word would perhaps belong to an Indo-European language different from Greek.

A. Panayotou summarizes some generally identified, through ancient texts and epigraphy, features[15]:

Phonology

- Occasional development of voiced aspirates (*bh, *dh, *gh) into voiced stops (b, d, g) (e.g. Βερενίκα, Attic Φερενίκη)

- Retention of */a:/ (e.g. Μαχάτας)

- [a:] as result of contraction [a:] + [ɔ:]

- Apocope of short vowels in prepositions in synthesis (παρκαττίθεμαι, Attic παρακατατίθεμαι)

- Syncope (hyphairesis) and diphthongization are used to avoid hiatus (e.g. Θετίμα, Attic Θεοτίμη)

- Occasional retention of the pronunciation [u] οf /u(:)/ in local cult epithets or nicknames (Κουναγίδας = Κυναγίδας)

- Raising of /ɔ:/ to /u:/ in proximity to nasal (e.g. Κάνουν, Attic Κάνων)

- Simplification of the sequence /ign/ to /i:n/ (γίνομαι, Attic γίγνομαι)

- Loss of aspiration of the consonant cluster /sth/ (> /st/) (γενέσται, Attic γενέσθαι)

Morphology

- First-declension masculine and feminine in -ας and -α respectively (e.g. Πεύκεστας, Λαομάγα)

- First-declension masculine genitive singular in -α (e.g. Μαχάτα)

- First-declension genitive plural in -ᾶν

- First person personal pronoun dative singular ἐμίν

- Temporal conjunction ὁπόκα

- Possibly, a non-sigmatic nominative masculine singular in the first declension (ἱππότα, Attic ἱππότης)

Onomastics

Anthroponymy

M. Hatzopoulos summarizes the Macedonian anthroponymy (that is names borne by people from Macedonia before the expansion beyond the Axius or people undoubtedly hailing from this area after the expansion) as follows:[16]

- Epichoric Greek names that either differ from the phonology of the introduced Attic or that remained almost confined to Macedonians throughout antiquity

- Panhellenic Greek names

- Identifiable non-Greek (Thracian, Illyrian and "native" -- that is names generally confined to Macedonian territory that aren't identified with any language, Greek or not) names

- Names without a clear Greek etymology that can't however be ascribed to any identifiable non-Greek linguistic group.

Common in the creation of ethnics is the use of -έστης, -εστός especially when derived from sigmatic nouns (ὄρος > Ὀρέστης but also Δῖον > Διασταί).[15]

Toponymy

The toponyms of Macedonia proper are generally Greek, though some of them show a particular Macedonian phonology that might set them apart and a few others are non-Greek.

Calendar

The Macedonian names of about half or more of the months of the ancient Macedonian calendar have a clear and generally accepted Greek etymology (e.g. Dios, Apellaios, Artemisios, Loos, Daisios), though some of the remaining ones have sometimes been considered to be Greek but showing a particular Macedonian phonology (e.g. Audunaios has been connected to "Haides" *A-wid and Gorpiaios/Garpiaios to "karpos" fruit).

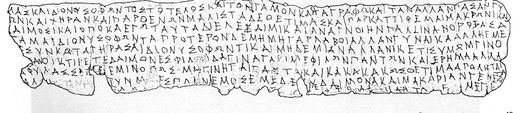

Epigraphy

Macedonian onomastics: the earliest epigraphical documents attesting substantial numbers of Macedonian proper names are the second Athenian alliance decree with Perdiccas II (~417-413 BC), the decree of Kalindoia,~335-300 BC) and seven curse tablets of the 4th c. BC bearing mostly names.[17][18]

The Pella curse tablet, a text written in a distinct Doric Greek dialect, found in 1986 and dated to between mid to early 4th century BC, has been forwarded as an argument that the ancient Macedonian language was a dialect of North-Western Greek, part of the Doric dialects.[19]

Hesychius Glossary

The below words of unknown date, out of the single Hesychius manuscript, are marked as Macedonian.For the words of Macedonian Amerias, see Glossary of Amerias. Terms that occur in epigraphy are transferred above.

- ἄβαγνα abagna 'roses amaranta (unwithered)' (Attic ῥόδα rhoda, Aeolic βρόδα broda roses). (LSJ: amarantos unfading. Amaranth flower. (Aeolic ἄβα aba 'youthful prime' + ἁγνός hagnos 'pure, chaste, unsullied) or epithet aphagna from aphagnizo 'purify'.[20] If abagnon is the proper name for rhodon rose, then it is cognate to Persian bāġ, 'garden', Gothic bagms 'tree' and Greek bakanon 'cabbage-seed'. Finally, a Phrygian borrowing is highly possible if we think of the famous Gardens of Midas, where roses grow of themselves (see Herodotus 8.138.2, Athenaeus 15.683)

- ἀβαρκνᾷ abarknai κομᾷ † τὲ Μακεδόνες Text Corrupted (komai? ἄβαρκνα abarkna hunger, famine.

- ἀβαρύ abarú 'oregano' (Hes. ὀρίγανον origanon) (LSJ: βαρύ barú perfume used in incense, Attic βαρύ barú 'heavy') (LSJ: amarakon sweet Origanum Majorana) (Hes. for origanon ἀγριβρόξ agribrox, ἄβρομον abromon, ἄρτιφος artiphos, κεβλήνη keblênê)

- ἀβλόη, ἀλογεῖ abloē, alogei Text Corrupted †<ἀβλόη>· σπένδε Μακεδόνες [<ἀλογεῖ>· σπεῖσον Μακεδόνες] spendô)

- ἀβροῦτες or ἀβροῦϜες abroûtes or abroûwes 'eyebrows' (Hes. Attic ὀφρῦς ophrûs acc. pl., ὀφρύες ophrúes nom., PIE *bhru-) (Lithuanian bruvis, Persian abru) (Koine Greek ophrudia, Modern Greek φρύδια frydia)

- ἀγκαλίς ankalis Attic 'weight, burden, load' Macedonian 'sickle' (Hes. Attic ἄχθος ákhthos, δρέπανον drépanon, LSJ Attic ἀγκαλίς ankalís 'bundle', or in pl. ἀγκάλαι ankálai 'arms' (body parts), ἄγκαλος ánkalos 'armful, bundle', ἀγκάλη ankálē 'the bent arm' or 'anything closely enfolding', as the arms of the sea, PIE *ank 'to bend') (ἀγκυλίς ankylis 'barb' Oppianus.C.1.155.)

- ἄδδαι addai poles of a chariot or car, logs (Attic ῥυμοὶ rhumoi) (Aeolic usdoi, Attic ozoi, branches, twigs) PIE *H₂ó-sd-o- , branch

- ἀδῆ adē 'clear sky' or 'the upper air' (Hes. οὐρανός ouranós 'sky', LSJ and Pokorny Attic αἰθήρ aithēr 'ether, the upper, purer air', hence 'clear sky, heaven')

- ἄδισκον adiskon potion, cocktail (Attic kykeôn)

- ἄδραια adraia 'fine weather, open sky' (Hes. Attic αἰθρία aithría, PIE *aidh-)

- Ἀέροπες Aeropes tribe (wind-faced) (aero- +opsis(aerops opos, Boeotian name for the bird merops)

- ἀκόντιον akontion spine or backbone, anything ridged like the backbone: ridge of a hill or mountain (Attic rhachis) (Attic akontion spear, javelin) (Aeolic akontion part of troops)

- ἀκρέα akrea girl (Attic κόρη korê, Ionic kourê, Doric/Aeolic kora, Arcadian korwa, Laconian kyrsanis (Ἀκρέα, epithet of Aphrodite in Cyprus, instead of Akraia, on the heights).

- ἀκρουνοί akrounoi 'boundary stones' nom. pl. (Hes. ὃροι hóroi, LSJ Attic ἄκρος ákros 'at the end or extremity', from ἀκή akē 'point, edge', PIE *ak 'summit, point' or 'sharp')

- ἀλίη alíē 'boar or boarfish' (Attic kapros) (PIE *ol-/*el- "red, brown" (in animal and tree names)[21] (Homeric ellos fawn, Attic elaphos deer, alkê elk)

- ἄλιζα aliza (also alixa) 'White Poplar' (Attic λεύκη leúkē, Thessalian alphinia, LSJ: ἄλυζα, aluza globularia alypum) (Pokorny Attic ἐλάτη elátē 'fir, spruce', PIE *ol-, *el- , P.Gmc. and Span. aliso 'alder')

- ἄξος axos 'timber' (Hes. Attic ὓλη hulê) (Cretan Doric ausos Attic alsos 'grove' little forest. (PIE *os- ash tree(OE.æsc ash tree), (Greek. οξυά oxya, Albanian ah, beech), (Armenian. haci ash tree)

- ἀορτής aortês, 'swordsman' (Hes. ξιφιστής; Homer ἄορ áor 'sword'; Attic ἀορτήρ aortēr 'swordstrap', modern Greek αορτήρ aortír 'riflestrap'; hence aorta) (According to Suidas: Many now say the knapsack ἀβερτὴ abertê instead of aortê. Both the object and the word [are] Macedonian.

- Ἀράντιδες Αrantides Erinyes (in dative ἀράντισιν ἐρινύσι) (Arae[22] name for Erinyes,arasimos accursed, araomai invoke, curse, pray or rhantizô sprinkle, purify.

- ἄργελλα argella 'bathing hut'. Cimmerian ἄργιλλα or argila 'subterranean dwelling' (Ephorus in Strb. 5.4.5) PIE *areg-; borrowed into Balkan Latin and gave Romanian argea (pl. argele), "wooden hut", dialectal (Banat) arghela "stud farm"); cf. Sanskrit argalā 'latch, bolt', Old English reced "building, house", Albanian argësh "harrow, crude bridge of crossbars, crude raft supported by skin bladders"

- ἀργι(ό)πους argiopous 'eagle' (LSJ Attic ἀργίπους argípous 'swift- or white-footed', PIE *hrg'i-pods < PIE *arg + PIE *ped)

- Ἄρητος Arētos epithet or alternative of Herakles (Ares-like)

- ἀρκόν arkon 'leisure, idleness' (LSJ Attic ἀργός argós 'lazy, idle' nom. sing., ἀργόν acc.)

- ἀρφύς arhphys (Attic ἱμάς himas strap, rope), (ἁρπεδών harpedôn cord, yarn; ἁρπεδόνα Rhodes, Lindos II 2.37).

- ἄσπιλος aspilos 'torrent' (Hes. χείμαῤῥος kheímarrhos, Attic ἄσπιλος áspilos 'without stain, spotless, pure')

- βαβρήν babrên lees of olive-oil (LSJ: βάβρηκες babrêkes gums, or food in the teeth, βαβύας babuas mud)

- βαθάρα bathara pukliê (Macedonian), purlos (Athamanian) (unattested; maybe food, atharê porridge, pyros wheat)

- βίῤῥοξ birrhox dense, thick (LSJ: βειρόν beiron)

- γάρκα garka rod (Attic charax) (EM: garkon axle-pin) (LSJ: garrha rod)

- γόλα gola or goda bowels, intestines (Homeric cholades) PIE: ghel-ond-, ghol-n•d- stomach; bowels[23]

- γοτάν gotan 'pig' acc. sing. (PIE *gwou- 'cattle', (Attic βοτόν botón ' beast', in plural βοτά botá 'grazing animals') (Laconian grôna 'sow' female pig, and pl. grônades) (LSJ: goi, goi, to imitate the sound of pigs) (goita sheep or pig)

- γυλλάς gyllas kind of glass (gyalas a Megarian cup)

- γῶψ gôps pl. gopes macherel (Attic koloios) (LSJ: skôps a fish) (Modern Greek gopa 'bogue' fish pl. gopes)

- δαίτας daitas caterer waiter (Attic daitros

- δάνος danos 'death', (Hes. Attic thánatos θάνατος 'death', from root θαν- than-), PIE *dhenh2- 'to leave, δανoτής danotês (disaster,pain) Sophocles Lacaenae fr.338[24]

- δανῶν danōn 'murderer' (Attic θανών thanōn dead, past participle)

- δάρυλλος darullos 'oak' (Hes. Attic δρῦς drûs, PIE *doru-)

- δρῆες drêes or δρῆγες drêges small birds (Attic strouthoi) (Elean δειρήτης deirêtês, strouthos, Nicander.Fr.123.) (LSJ: διγῆρες digêres strouthoi, δρίξ drix strouthos)

- δώραξ dôrax spleen, splên (Attic θώραξ thôrax chest, corslet

- ἐπιδειπνίς epideipnis Macedonian dessert

- Ζειρηνίς Zeirênis epithet or alternative for Aphrodite (Seirênis Siren-like)

- Ἠμαθία Êmathia ex-name of Macedonia, region of Emathia from mythological Emathus (Homeric amathos êmathoessa, river-sandy land, PIE *samadh.[25] Generally the coastal Lower Macedonia in contrast to mountainous Upper Macedonia. For meadow land (mē-2, m-e-t- to reap), see Pokorny.[26]

- Θαῦλος Thaulos epithet or alternative of Ares (Θαύλια Thaulia 'festival in Doric Tarentum, θαυλίζειν thaulizein 'to celebrate like Dorians', Thessalian Ζεὺς Θαύλιος Zeus Thaulios, the only attested in epigraphy 10 times, Athenian Ζεὺς Θαύλων Zeus Thaulôn, Athenian family Θαυλωνίδαι Thaulônidai

- Θούριδες Thourides Nymphs Muses (Homeric thouros rushing, impetuous.

- ἰζέλα izela wish, good luck (Attic agathêi tychêi) (Doric bale, abale, Arcadian zele) (Cretan delton agathon)[27] or Thracian zelas wine.

- ἴλαξ ílax 'the holm-oak, evergreen or scarlet oak' (Hes. Attic πρῖνος prînos, Latin ilex)

- ἰν δέᾳ in dea midday (Attic endia, mesêmbria) (Arcadian also in instead of Attic en)

- κἄγχαρμον kancharmon having the lance up τὸ τὴν λόγχην ἄνω ἔχον (Hes. ἄγχαρμον ancharmon ἀνωφερῆ τὴν αἰχμήν <ἔχων> Ibyc? Stes?) having upwards the point of a spear)

(κἄ, Crasis) kai and,together,simultaneously + anô up (anôchmon hortatory password)

- κάραβος karabos

- Macedonian 'gate, door' (Cf. karphos any small dry body,piece of wood (Hes. Attic 'meat roasted over coals'; Attic karabos 'stag-beetle'; 'crayfish'; 'light ship'; hence modern Greek καράβι karávi)

- 'the worms in dry wood' (Attic 'stag-beetle, horned beetle; crayfish')

- 'a sea creature' (Attic 'crayfish, prickly crustacean; stag-beetle')

- καρπαία karpaia Thessalo-Macedonian mimic military dance (see also Carpaea) Homeric karpalimos swift (for foot) eager, ravenous.

- κίκεῤῥοι kí[k]erroi 'pale ones (?)' (Hes. Attic ὦχροι ōkhroi, PIE *k̂ik̂er- 'pea') (LSJ: kikeros land crocodile)

- κομμάραι kommarai or komarai crawfishes (Attic karides) (LSJ: kammaros a kind of lobster, Epicharmus.60, Sophron.26, Rhinthon.18:-- also kammaris, idos Galen.6.735.) (komaris a fish Epicharmus.47.)

- κόμβοι komboi 'molars' (Attic γομφίοι gomphioi, dim. of γόμφος gomphos 'a large, wedge-shaped bolt or nail; any bond or fastening', PIE *gombh-)

- κυνοῦπες kynoupes or kynoutos bear (Hesychius kynoupeus, knoupeus, knôpeus) (kunôpês dog-faced) (knôps beast esp. serpent instead of kinôpeton, blind acc. Zonar (from knephas dark) (if kynoutos knôdês knôdalon beast)

- λακεδάμα lakedáma ὕδωρ ἁλμυρὸν ἄλικι ἐπικεχυμένον salty water with alix, rice-wheat or fish-sauce.(Cf.skorodalmê 'sauce or pickle composed of brine and garlic'). According to Albrecht von Blumenthal,[13] -ama corresponds to Attic ἁλμυρός halmurós 'salty'; Cretan Doric hauma for Attic halmē; laked- is cognate to Proto-Germanic *lauka[28] leek, possibly related is Λακεδαίμων Laked-aímōn, the name of the Spartan land.

- λείβηθρον leíbēthron 'stream' (Hes. Attic ῥεῖθρον rheîthron, also λιβάδιον libádion, 'a small stream', dim. of λιβάς libás; PIE *lei, 'to flow'); typical Greek productive suffix -θρον (-thron) (Macedonian toponym, Pierian Leibethra place/tomb of Orpheus)

- ματτύης mattuês kind of bird (ματτύη mattuê a meat-dessert of Macedonian or Thessalian origin) (verb mattuazo to prepare the mattue) (Athenaeus)[29]

- παραός paraos eagle or kind of eagle (Attic aetos, Pamphylian aibetos) (PIE *por- 'going, passage' + *awi- 'bird') (Greek para- 'beside' + Hes. aos wind) (It may exist as food in Lopado...pterygon)

- περιπέτεια peripeteia or περίτια peritia Macedonian festival in month Peritios. (Hesychius text περί[πε]τ[ε]ια)

- ῥάματα rhamata bunch of grapes (Ionic rhagmata, rhages Koine rhôgmata, rhôges, rhax rhôx)

- ῥοῦτο rhouto this (neut.) (Attic τοῦτο touto)

- ταγόναγα tagonaga Macedonian institution, administration (Thessalian ταγὸς tagos commander + ἄγωagô lead)

Other Sources

- αἰγίποψ aigipops eagle (EM 28.19) (error for argipous? maybe goat-eater? aix ,aigos + pepsis digestion) (Cf.eagle chelônophagos turtle-eater)[30]

- ἀργυρὰσπιδες argyraspides (wiki Argyraspides) chrysaspides and chalkaspides (golden and bronze-shielded)[31]

- δράμις dramis a Macedonian bread (Thessalian bread daratos)(Athamanian bread dramix. (Athenaeus)[32]

- καυσία kausia felt hat used by Macedonians, forming part of the regalia of the kings.

- κοῖος koios number (Athenaeus[33] when talking about Koios, the Titan of intelligence; and the Macedonians use koios as synonymous with arithmos (LSJ: koeô mark, perceive, hear koiazô pledge, Hes. compose s.v. κοίασον, σύνθες) (Laocoön, thyoskoos observer of sacrifices, akouô hear) (All from PIE root *keu[34] to notice, observe, feel; to hear.

- πεζέταιροι pezetairoi (wiki Pezhetairoi), Hetairidia, Macedonian religious festival (Attic πεζοί,πεζομάχοι) (Aeolic πέσδοι)[35]

- Πύδνα Púdna, Pydna toponym (Pokorny[36] Attic πυθμήν puthmēn 'bottom, sole, base of a vessel'; PIE *bhudhnā; Attic πύνδαξ pýndax 'bottom of vessel') (Cretan,Pytna[37]Hierapytna, Sacred Pytna[38]

- σίγυνος sigynos spear (Cypriotic sigynon) (Illyrian sibyne) (Origin: Illyrian acc. to Fest.p. 453 L., citing Ennius) (Cyprian acc. to Herodotus and Aristotle[39] Il. cc., Scythian acc. to Sch.Par.A.R.4.320 (cf. 111)

- σφύραινα sphuraina, hammer-fish sphyraena (Strattis,Makedones (fr. 28) - (Attic.κέστρα, kestra) (cestra, needle-fish (modern Greek fish σφυρίδα, sfyrida)

- ὐετής uetês of the same year Marsyas (Attic autoetês, Poetic oietês)

- χάρων charôn lion (Attic/Poetic fierce, for lion, eagle instead of charopos, charops bright-eyed)[40]

Proposed

A number of Hesychius words are listed orphan; some of them have been proposed as Macedonian[41]

- ἀγέρδα agerda wild pear-tree (Attic ἄχερδος acherdos).

- ἀδαλός adalos charcoal dust (Attic αἴθαλος aithalos, ἄσβολος asbolos)

- ἄδδεε addee imp. hurry up ἐπείγου (Attic thee of theô run)

- ἄδις adis 'hearth' (Hes. ἐσχάρα eskhára, LSJ Attic αἶθος aîthos 'fire, burning heat')

- αἰδῶσσα aidôssa (Attic aithousa portico, corridor, verandah, a loggia leading from aulê yard to prodomos)

- βάσκιοι baskioi 'fasces' (Hes. Attic δεσμοὶ φρῡγάνων desmoì phrūgánōn, Pokorny βασκευταί baskeutaí, Attic φασκίδες phaskídes, Attic φάσκωλος pháskōlos 'leather sack', PIE *bhasko-)

- βίξ bix sphinx (Boeotian phix), (Attic sphinx)

- δαλάγχα dalancha sea (Attic thalatta) (Ionic thalassa)

- δεδάλαι dedalai package, bundle (Attic dethla, desmai)

- ἐσκόροδος eskorodos tenon (Attic tormos σκόρθος skorthos tornos slice, lathe)

- Εὐδαλαγῖνες Eudalagines Graces Χάριτες (Attic Εὐθαλγῖνες Euthalgines)

- κάναδοι kanadoi 'jaws' nom. pl. (Attic γνάθοι gnathoi, PIE *genu, 'jaw') (Laconian καναδόκα kanadoka notch (V) of an arrow χηλὴ ὀϊστοῦ)

- λαίβα laiba shield (Doric λαία laia, λαῖφα laipha) (Attic aspis)

- λάλαβις lalabis storm (Attic lailaps)

- ὁμοδάλιον homodalion isoetes plant (θάλλω thallô bloom)

- ῥουβοτός rhoubotos potion (Attic rhophema) rhopheo suck, absorb rhoibdeô suck with noise.

Macedonian in Classical sources

Among the references that have been discussed as possibly bearing some witness to the linguistic situation in Macedonia, there is a sentence from a fragmentary dialogue, apparently between an Athenian and a Macedonian, in an extant fragment of the 5th century BC comedy 'Macedonians' by the Athenian poet Strattis (fr. 28), where a stranger is portrayed as speaking in a rural Greek dialect. His language contains expressions such as ὕμμες ὡττικοί for ὑμείς αττικοί "you Athenians", ὕμμες being also attested in Homer, Sappho (Lesbian) and Theocritus (Doric), while ὡττικοί appears only in "funny country bumpkin" contexts of Attic comedy.[42]

Another text that has been quoted as evidence is a passage from Livy (lived 59 BC-14 AD) in his Ab urbe condita (31.29). Describing political negotiations between Macedonians and Aetolians in the late 3rd century BC, Livy has a Macedonian ambassador argue that Aetolians, Acarnanians and Macedonians were "men of the same language".[43] This has been interpreted as referring to a shared North-West Greek speech (as opposed to Attic Koiné).[44]

Quintus Curtius Rufus, Philotas's trial.[45]

Over time, "Macedonian" (μακεδονικός), when referring to language (and related expressions such as μακεδονίζειν; to speak in the Macedonian fashion) acquired the meaning of Koine Greek.[46]

Contributions to the Koine

Despite the Macedonians' important role in the formation of the Koine, Macedonian itself contributed few elements to the dialect, such as military terminology (διμοιριτης, ταξιαρχος, υπασπισται etc.) and, possibly, the suffix "-issa" which became productive in Medieval Greek.

See also

- Ancient Greek

- Ancient Greek dialects

- Proto-Greek language

- Amerias

- Macedon

- Ancient Greece

- Phrygian language

- Thracian language

- Hellenic languages

Notes

- ^ The Oxford English Dictionary (1989), Macedonian, Simpson J. A. & Weiner E. S. C. (eds), Oxford: Oxford University Press, Vol. IX, ISBN 0-19-861186-2 (set) ISBN 0-19-861221-4 (vol. IX) p. 153

- ^ Webster's Third New International Dictionary of the English Language Unabridged (1976), Macedonian, USA:Merriam-Webster, G. & C. Merriam Co., vol. II (H - R) ISBN 0-87779-101-5

References

- ↑ Eugene N. Borza (1992) In the Shadow of Olympus: The Emergence of Macedon, p. 94 (citing Hammond); G. Horrocks, Greek: A History of the Language and its Speakers (1993), ch.4.1.

- ↑ Michael G. Clyne, Sandra Kipp (2006). Tiles in a multilingual mosaic: Macedonian, Filipino and Somali in Melbourne. Pacific Linguistics. p. 21. ISBN 9780858835696. http://books.google.com/books?id=oEdiAAAAMAAJ&q=%22ancient+macedonian+language%22&dq=%22ancient+macedonian+language%22&lr=.

- ↑ Lewis, D. M.; Boardman, John (2000). The Cambridge ancient history, 3rd edition, Volume VI. Cambridge University Press. p. 730. ISBN 9780521233484. http://books.google.com/books?id=vx251bK988gC&pg=RA7-PA831&dq=ancient+cavalry+macedonian+cavalry&lr=&client=firefox-a#PRA6-PA750,M1.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 B. Joseph (2001): "Ancient Greek". In: J. Garry et al. (eds.) Facts about the world's major languages: an encyclopedia of the world's major languages, past and present. Online paper

- ↑ Mallory, J.P. (1997). Mallory, J.P. and Adams, D.Q. (eds.). ed. Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Chicago-London: Fitzroy Dearborn. pp. 361. ISBN 1-884964-98-2.

- ↑ A. Meillet [1913] 1965, Aperçu d'une histoire de la langue grecque, 7th ed., Paris, p. 61. I. Russu 1938, in Ephemeris Dacoromana 8, 105-232. Quoted after Brixhe/Panayotou 1994: 209.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Masson, Olivier (2003) [1996]. "[Ancient] Macedonian language". In Hornblower, S. and Spawforth A. (eds.). The Oxford Classical Dictionary (revised 3rd ed. ed.). USA: Oxford University Press. pp. 905–906. ISBN 0-19-860641-9.

- ↑ Hammond, N.G.L (1993) [1989]. The Macedonian State. Origins, Institutions and History (reprint ed. ed.). USA: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-814927-1.

- ↑ Ahrens, F. H. L. (1843), De Graecae linguae dialectis, Göttingen, 1839-1843 ; Hoffmann, O. Die Makedonen. Ihre Sprache und ihr Volkstum, Göttingen, 1906.

- ↑ The Linguist List is classifying ancient Macedonian with Greek (all known ancient and modern dialects) under a Hellenic supertree.

- ↑ Exceptions to the rule:

- ἀρφύς arhphys Macedonian (Attic ἁρπεδών harpedôn cord, yarn)

- βάγαρον bagaron (Attic χλιαρόν chliaron 'warm') (cf. Attic phôgô 'roast') (Laconian)

- βώνημα bônêma speech (Homeric, Ionic eirêma eireo) (cf. Attic phônêma sound, speech) (Laconian)

- κεβλὴ keblê Callimachus Fr.140 Macedonian κεβ(α)λή keb(a)lē versus Attic κεφαλή kephalē ('head')

- κεβλήπυρις keblēpyris ('red-cap bird'), (Aristophanes Birds)

- κεβλήγονος keblêgonos born from the head, Euphorion 108 for Athena, with its seed in its head Nicander Alexipharmaca 433.

- πέχαρι pechari deer (Laconian berkios) Amerias

- Ὑπερβέρετος Hyperberetos Cretan month June, Macedonian September Hyperberetaios (Hellenic Calendars) (Attic hyperpheretês supreme, hyperpherô transfer,excel)

- ↑ Greek Questions 292e - Question 9 - Why do Delphians call one of their months Bysios [1].

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Albrecht von Blumenthal, Hesychstudien, Stuttgart, 1930, 21.

- ↑ Olivier Masson, "Sur la notation occasionnelle du digamma grec par d'autres consonnes et la glose macédonienne abroutes", Bulletin de la Société de linguistique de Paris, 90 (1995) 231-239. Also proposed by O. Hoffmann and J. Kalleris.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 A history of ancient Greek: from the beginnings to late antiquity, Maria Chritē, Maria Arapopoulou, Cambridge University Press (2007), p. 439-441

- ↑ Greek Personal Names: Their Value as Evidence, Elaine Matthews, Simon Hornblower, Peter Marshall Fraser, British Academy, Oxford University Press (2000), p. 103

- ↑ Athens, bottom-IG I³ 89 -- Kalindoia-Meletemata 11 K31 -- Pydna-SEG 52:617,I (6) till SEG 52:617,VI - Mygdonia-SEG 49:750

- ↑ Greek Personal Names: Their Value as Evidence [2] by Simon Hornblower, Elaine Matthews

- ↑ O. Masson (1996).

- ↑ Les anciens Macedoniens. Etude linguistique et historique by J. N. Kalleris

- ↑ Online Etymology Dictionary

- ↑ ARAE: Greek goddesses or spirits of curses; mythology: ARAI

- ↑ Pokorny

- ↑ Poetae scenici graeci, accedunt perditarum fabularum fragmenta

- ↑ Pokorny Query madh

- ↑ Pokorny's Dictionary

- ↑ (Izela) Die Makedonen, Ihre Sprache und Ihr Volkstum [3] by Otto Hoffmann

- ↑ Online Etymology Dictionary

- ↑ Deipnosophists 14.663-4 (pp. 1059-1062)

- ↑ Kalleris, p. 238-240

- ↑ Kalleris, p. 108

- ↑ Athenaeus Deipnosophists 3.114b.

- ↑ Deipnosophists 10.455e.

- ↑ Pokorny [4], Gerhard Köbler [5]

- ↑ Kalleris, p. 172-179, 242

- ↑ Pokorny,Pudna

- ↑ Zeitschrift der Deutschen morgenländischen Gesellschaft

- ↑ The Dorians in Archaeology by Theodore Cressy Skeat [6]

- ↑ Poetics (Aristotle)-XXI [7]

- ↑ Kalleris, p. 274

- ↑ Otto Hoffmann, p. 270 (bottom)

- ↑ Steven Colvin, Dialect in Aristophanes and the politics of language in Ancient Greek, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999, p. 279.

- ↑ Livy 31.29.15 (in Latin).

- ↑ A. Panayotou: The position of the Macedonian dialect. In: Maria Arapopoulou, Maria Chritē, Anastasios-Phoivos Christides (eds.), A History of Ancient Greek: From the Beginnings to Late Antiquity, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007, pp. 433-458 (Google Books).

- ↑ E. Kapetanopoulos. "Alexander’s Patrius Sermo in the Philotas Affair", The Ancient World 30 (1999), pp. 117-128. (PDF or HTM)

- ↑ C. Brixhe, A. Panayotou, 1994, «Le Macédonien» in Langues indo-européennes, p. 208

Further reading

- Brixhe C., Panayotou A. (1994) Le Macédonien in Bader, F. (ed.) Langues indo-européennes, Paris:CNRS éditions, 1994, pp 205–220. ISBN 2-271-05043-X

- Chadwick, J. The Prehistory of the Greek Language. Cambridge, 1963.

- Crossland, R. A., "The Language of the Macedonians", CAH III.1, Cambridge 1982

- Hammond, Nicholas G.L. "Literary Evidence for Macedonian Speech", Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, Vol. 43, No. 2. (1994), pp. 131–142.

- Hatzopoulos, M. B. Le Macedonien Nouvelles Donnees et Theories Nouvelles in Ancient Macedonia, Sixth International Symposium, Volume 1, Institute for Balkan Studies (1999)

- Kalleris, Jean. Les Anciens Macédoniens, étude linguistique et historique. Institut Francais d'Athénes, 1988

- Katičić, Radoslav. Ancient Languages of the Balkans. The Hague; Paris: Mouton, 1976.

- Neroznak, V. Paleo-Balkan languages. Moscow, 1978.

- Rhomiopoulou, Katerina. An Outline of Macedonian History and Art. Greek Ministry of Culture and Science, 1980.

- Die Makedonen: Ihre Sprache und ihr Volkstum by Otto Hoffmann

External links

- The speech of the ancient Macedonians, in the light of recent epigraphic discoveries

- The Linguist List: Family tree of Hellenic languages

- Jona Lendering, Ancient Macedonia web page on livius.org

- Greek Inscriptions from ancient Macedonia (Epigraphical Database)

- Heinrich Tischner on Hesychius' words

- www.sil.org: ISO639-3, entry for Ancient Macedonian (XMK)